2015 Federal Projection - Methodology

election-atlas.ca is introducing a seat projection model for the 2015 federal election. The plan is to fine-tune or update it at least once a week between now and the October 19 election.

I started working on a projection model for the 2014 Quebec election and shared it with a few friends and fellow election geeks, and have been fine-tuning it for every provincial election since.

Keep in mind that my background is in engineering, not statistics, and I probably broke the scientific method somewhere along the way. I'm no Nate Silver.

Except in very rare cases, these projections are not based on any individual riding polls, but on extrapolating national or regional polls down to the local level. They should not be used to predict actual vote shares in each riding, but may give a general idea of local trends.

As in all cases, this model is only as good as the poll data that goes into it. If the BBC's exit poll of 18,000 people can misjudge the UK Conservative vote by the difference between a majority and minority, then a subsample in Manitoba in July can do even worse.

For the major parties (Conservatives, NDP, Liberals, Greens and Bloc) I calculate the party standing for each riding using the following formula:

Each of these is described below:

2011 redistributed result

This is simply the result of the 2011 election adjusted for the new riding boundaries, as determined by Elections Canada in their Transposition of Votes. In a couple of cases like Labrador, I used the results of the 2013 by-election instead as I feel its results more genuinely reflect the political realities of that riding. There were also cases like the riding of Portneuf--Jacques-Cartier in Quebec, where the Conservatives did not run a candidate in 2011 in favour of endorsing independent André Arthur. In that case, I simply used Arthur's share as the Tories' starting point.

Regional Coefficient

This is the average of all polls (weighted for sample size) for each region of the country. For the 3 northern seats, I use the national numbers with the Bloc Quebecois removed.

To smooth out the effects of poll errors (the infamous "20th out of 20") and small sample sizes, polls are weighted for time. The most recent poll by each company is worth 1/2 of that company's score; the second most recent, 1/4; the third-most recent, 1/8; etc. If the company has not released polling numbers within the last week, their weight is discounted by half, if there have been none within the last two weeks, it is removed from the equation entirely.

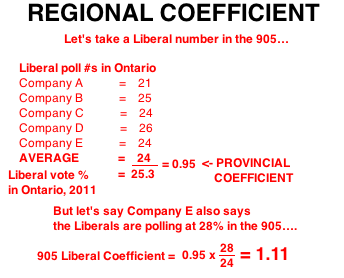

The regional coefficient for each party in each province is the average of these scores for all companies in the field within the last 2 weeks, divided by the provincial vote share for that party in 2011.

I also take sub-regional samples into account where available. For instance, while all other polling companies lump Atlantic Canada together as one region, Corporate Research Associates breaks the region down province-by-province. If CRA says the Conservatives are polling at 20% region-wide, but in New Brunswick at 30%, I multiply the Conservative regional coefficient by an additional 1.5 for New Brunswick.

Regional coefficient explained. Like my Paintbrush skills?

Local Coefficient

This can be somewhat arbitrary, and a lot of the time just comes down to gut instinct. This number is usually 1 (so no change), but can be adjusted up or down based on factors specific to that riding. For instance, if an MP is retiring, that party's share is marked down (in some cases by 30%) based on his/her name recognition, longevity and how well that party does in neighbouring ridings. For instance, the departure of a Peter MacKay or James Moore would cause a greater drop in the Conservative share than the departure of a random backbencher.

If an MP with a strong personal vote was defeated in 2011 (e.g. Gilles Duceppe), his or her party can also be marked down. If it can be known or believed that the bulk of that party's vote share will be going specifically to another party, that party's coefficient will be increased accordingly. Star candidates can cause a party's local coefficient to go up.

Also, there are other ridings where a party that outperformed its regional vote 4 years ago might not do so this time. Think of the so-called "promiscuous progressives". This was especially evident in the Alberta election, where in some ridings the progressive vote switched en masse from the Liberals in 2012 to the NDP in 2015. The Liberal vote in some Vancouver ridings may become a good federal example, and there are some where I have given 10-20% of it to the NDP.

There are also cases of MPs switching parties or running as independents. Take the case of Jean-François Fortin, who quit the Bloc Quebecois to form the new Forces et Démocratie party. I have assigned Fortin roughly 2/3 of the BQ vote from 2011, based on the most similar situation I could find (Jean-Martin Aussant quitting the PQ to form Option Nationale in 2012). Or Bruce Hyer, who left the NDP to join the Green Party. I gave him the same share of the NDP vote that ex-Liberal Blair Wilson took with him to the Greens in 2008.

Smaller Parties and Independents

This is the trickiest part. Independent candidates are hard to gauge without polls at the local riding level. MPs who leave their party meet with mixed results. Bill Casey quit the Tory caucus in 2008 and won a bigger victory as an independent; Helena Guergis was kicked out in 2011 and went on to finish a distant third.

And then there are the times when someone who loses a party nomination runs as an indy. A lot of times their runs play spoiler at best; in rare cases they do just as well as the official candidate. A good example is Edmonton-Sherwood Park, where an independent who lost the Conservative nomination almost defeated Tim Uppal in 2008 - and then again in 2011.

As a general rule, I have initially given independent candidates with a known party affiliation somewhere between 5-20% of that party's 2011 vote. That can and will change based on local media coverage and polls (if any) during the campaign.

The launch of Forces et Démocratie also complicates things this year. Outside of Fortin and Larose, I have arbitrarily assigned other FD candidates in Quebec a total of 5% of the BQ 2011 + 5% of the NDP 2011 vote. This usually comes out to 3-4% overall, roughly the same as the Green Party, and roughly matches up with the 1% "other" number seen in most polls in Quebec.

For minor parties (Libertarian, Christian Heritage, Communist, etc) I have assigned all candidates a vote percentage equal to the national share in ridings where they ran in the last election. For instance, Libertarian Party candidates averaged 0.5% of the vote in their ridings in 2011, so I'm assigning all Libertarian candidates 0.5% this time around.